Imagine entering a college campus without hearing the sounds of students, faculty, and staff chattering in the student union or student groups recruiting students outside on the sidewalk.

This is the reality for anywhere from 25,000 to 27,000 hard of hearing, deaf, and Deaf students enrolled in higher education in the United States.

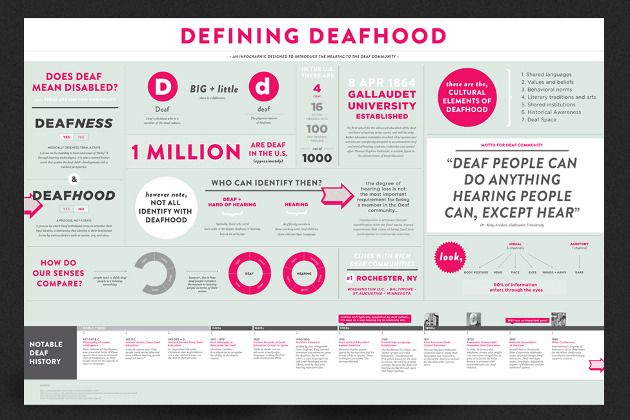

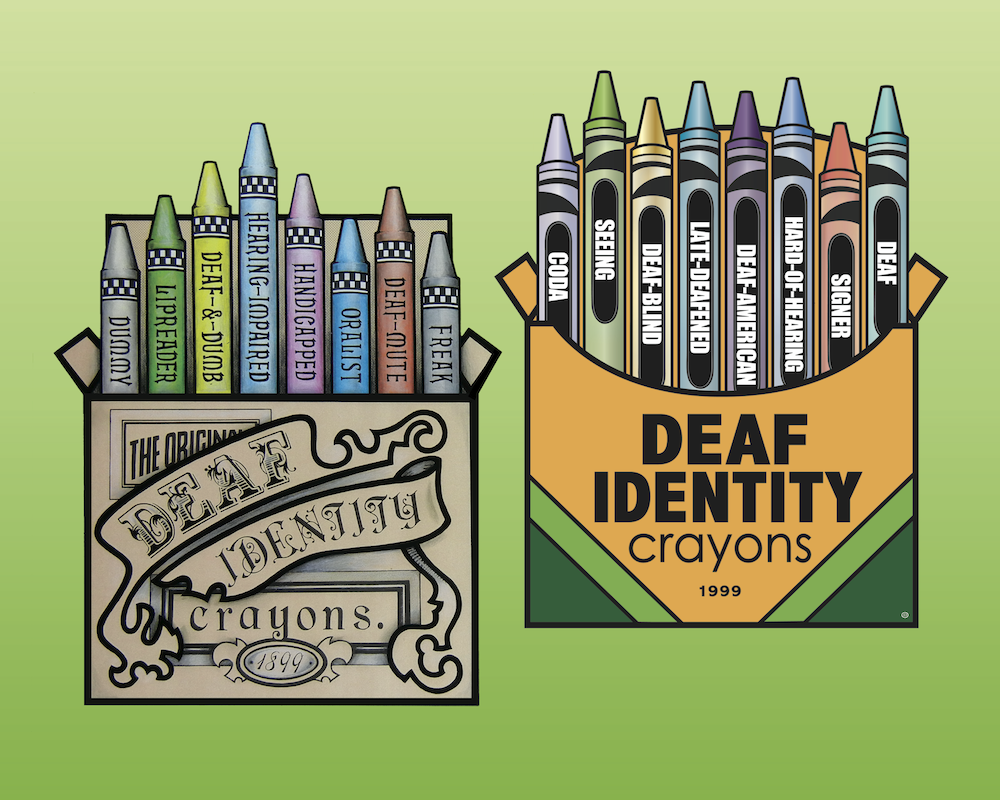

For the purpose of this article, the terms hard of hearing, deaf, and Deaf may be used to talk about this population of students, while hearing impairments will be used as a general term to describe all three. I will also define hard of hearing and deaf as “individuals with a range of hearing loss,” and Deaf as students “who identify as culturally Deaf” (Miller, p. 16, 2007).

The education of d/Deaf individuals has faced many barriers throughout history and continues to need advocates to further the advancement of this population’s educational needs.

Deaf education has come a long way from having institutions with names like the “Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb and Blind.” However, this name will forever be part of Gallaudet University’s history — the only university designed for deaf students — memorializing the path that deaf education has traveled.

It was not until 1964 that oral education of deaf individuals was labeled a dismal failure, and it is still part of the legislative and cultural battle of many advocates who seek to improve deaf education. You can read more about the LEAD-K campaign, which aims to bring awareness to the necessary role of utilizing American Sign Language (ASL) with deaf children. To see a full timeline of deafness and education in the world visit this timeline compiled by the Gallaudet University Archives.

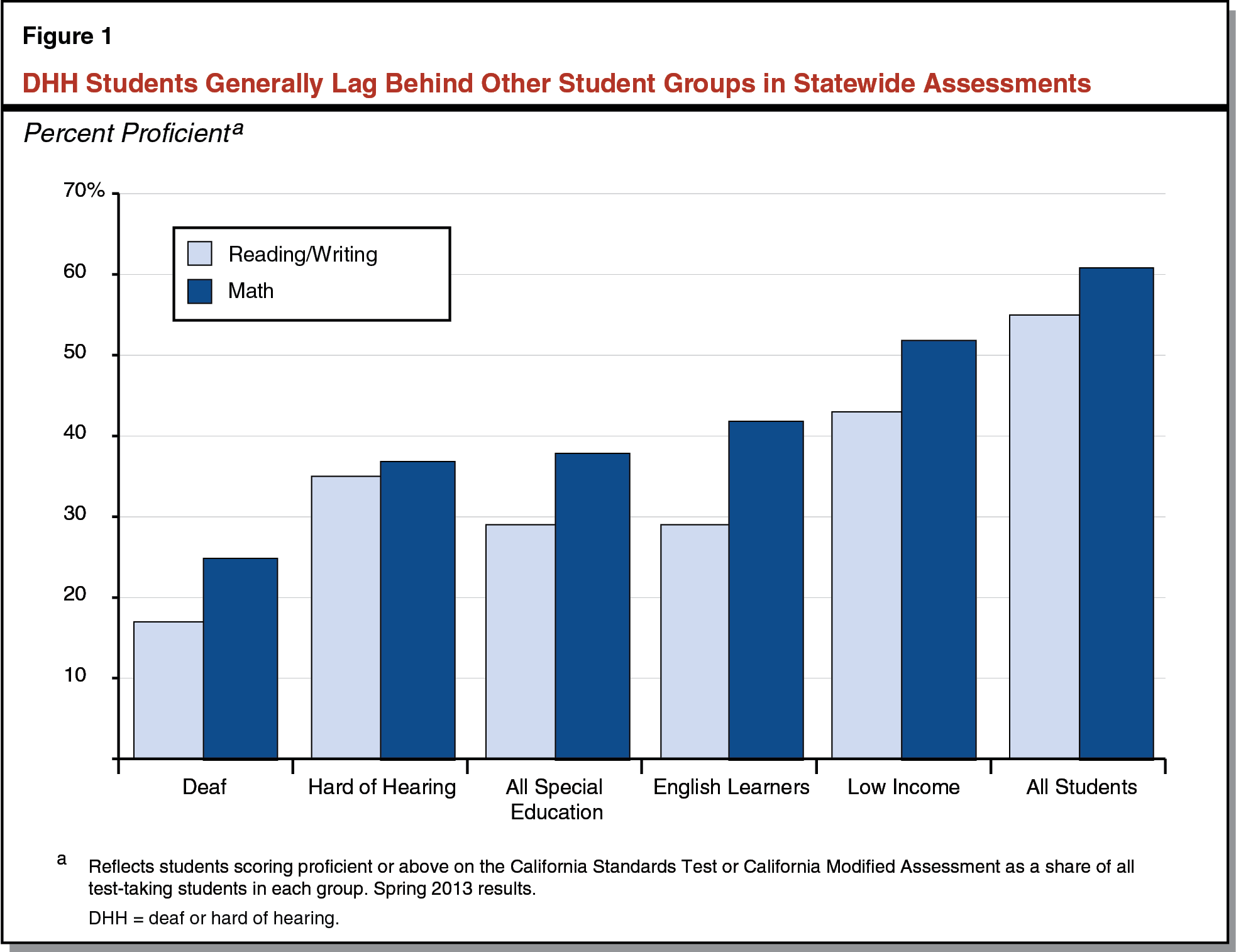

Due to the rise in the number of students with hearing impairments attending predominantly-hearing institutions, coupled with a 25% graduation rate from institutions of higher education, I believe it is important to shed some light on this population of students.

The issues facing students with hearing impairments is permeated with the question of what it means to be deaf in the United States and what it means to be deaf in higher education.

The Deaf Cultural Identity Scale developed in 1997 by Robin Gordon assigns four types of identification for deaf students: Hearing, marginal, immersion, and bicultural. Among d/Deaf and hard of hearing students, there is a wide diversity of how they experience and work with their deafness.

It is crucial that student affairs practitioners are aware of the diversity among this population of students. In this article, I want to examine the following three areas: Educational backgrounds, forms of assistance, and mentorship.

Educational backgrounds

The history of deaf education in the United States is marked with differing opinions on the best pedagogy for instructing students with hearing impairments. These differences have ranged from teaching deaf students to be oral or using American Sign Language (ASL), to a major current debate of deaf schools or mainstreamed programs.

Currently 75% of the d/Deaf and hard of hearing students in the United States participate in a mainstream K-12 program (Miller, 2007). That means 75% of students with a hearing impairment spend their time in a system where they are the only deaf student.

Some may argue that this educational background would prepare students for a career at a predominately-hearing institution, but research shows that hearing-impaired students often feel isolated in higher education (Nobel, 2010).

In student affairs, we know that students are more likely to succeed when they are connected to the campus community, so we need to work to find avenues to connect our campus communities. They need to be invited, we need to be patient, and we need to not make assumptions. We have to recognize that deafness is cultural and tied to one’s identity.

With this, we should also be prepared to support students along this identity development.

Forms of assistance

There are several different ways a student with a hearing impairment may get accommodations in higher education. The type of accommodation that the student chooses and how they perceive those accommodations will largely rest on their experiences with language and what type of educational background they have had.

Another determining factor in choosing a form of assistance is comfort and visibility of the assisting device.

While those students who identify culturally as Deaf and utilize ASL may be more inclined to use an interpreter, those students who don’t identify that way may prefer using technological support such as Computer-Assisted Real-time Transcription (CART) (Miller, 2007).

Using assistance generally does not leave the student any room to determine who knows about their deafness, putting them in a vulnerable situation where the student will have to trust their professor and peers, which may not always be the situation.

Convertino, Marschark, Sapere, Sarchet, and Zupan (2009) found that this level of identity-revealing leaves students feeling insecure in the classroom setting and in a more vulnerable place to be asked questions by their peers and professors.

Deaf students also believe that the professor will automatically place them at a lower standard in the class when their deafness is identified. There are many factors that impact this, ranging from societal perceptions of deafness and disabilities to feeling behind academically.

As professionals working in higher education, we must commit to helping combat this stigma.

We must realize that these students come into our classrooms, residence halls, and campus events with these insecurities. We must commit to making our events accessible and be willing to be flexible to embrace these students within our campus communities. I challenge professionals to take this a step further and to find ways to support and lift these students up.

For example, I am the son of Deaf parents, I know American Sign Language, and I am always acutely aware of students who come onto the campus I work at who are deaf or know sign language.

This past year, I had the opportunity to have one Deaf student and one hearing student with deaf parents (like me) who wanted to start an ASL teaching language group. Serving as their advisor has been one of the best parts of my year. When working with this population if we can find small ways to “go out of our way” to support them, it can go a really long way.

Mentorship

With the staggering reality that only 25% of deaf students enter higher education comes the fact that there are very few role models of matriculated deaf adults for these students to look up to as role models or mentors.

Boutin (2005) also identifies that deaf students typically enter higher education without a declared major and often without giving thought to declaring a major. In a 2004 study by Foster and MacLeod, the authors found that the role of a mentor was crucial in developing self-esteem and advocacy in deaf students (Miller, 2007).

Historically, higher paying jobs have been closed to deaf individuals, and since deaf students are in a hearing culture most of the time, they are more likely to see hearing individuals in careers (Allen, 1994).

We must work to provide these students with mentors — this is crucial to their success within higher education. These students need to be connected with professionals in their area of study and, if at all possible, with deaf adults as well. This mentoring relationship has the power to truly show these students that their future career plans are possible, even if they have never seen someone who looks like them in that role before.

The d/Deaf or hard-of-hearing student may face many barriers on their way to higher education, but it is next to impossible to assign a blanket experience over each student or even develop a list of services they will absolutely need.

Students with hearing impairments are a complex group of people with varying cultural experiences that will shape their perception of higher education and their own deaf identity.

Student affairs practitioners have the responsibility to understand that there are many factors impacting a deaf student and the aforementioned are only a few of the influences. How do you make your work inclusive to students with hearing impairments?