In higher education, we must be concerned with student learning and development.

After all, we’re in the business of facilitating opportunities and a supportive environment for those things. If our internal reasons were not enough, the increased scrutiny on higher education calls us to measure and demonstrate how effective we are in our efforts.

To do that, however, we must first be able to articulate what learning looks like.

Whatever you call them – learning goals, learning objectives, outcome statements, learning outcomes (my go-to) – we should be able to indicate the knowledge or skills we intend students to gain.

The good news is there are general elements to include in naming what students will know, think, or do as a result of engaging with us.

4 essential elements of learning outcomes:

1. Who is expected to learn?

While we are talking about students, that’s a big umbrella that includes lots of folks. Are you primarily concerned with students who live in your residence halls (e.g., residence life)? Do you serve newly admitted students (e.g., orientation or first-year experience)?

2. What learning is expected?

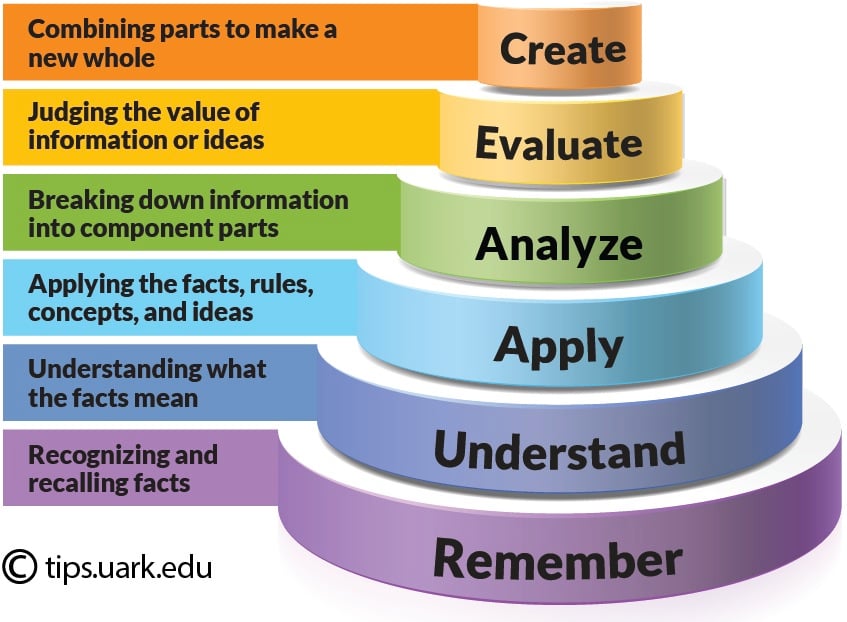

Name what students will be gaining or demonstrating. This is where “know” and “understand” generally are not helpful. I can know/understand something enough to summarize it, articulate how it resonates with them, and/or apply it to taking future action.

I would go about measuring each of those elements differently, so it would save time and add clarity to my outcome statement if I skipped “know” or “understand” and instead used more specific verbs and phrases. Look to your favorite learning taxonomy to help determine terms.

3. When/where is learning expected?

Because learning is multifaceted, multiple interventions may be required before learning occurs. What should students be able to demonstrate after attending one workshop? Would students need to meet at least twice with a career coach to prep a resume and cover letter for a job application?

4. Why is learning expected?

Institutions have specific interventions designed to promote learning and development. Those efforts align or contribute to larger goals for the student or operations for the institution. They provide context for the extent that learning is occurring for the student.

Let’s try this out with an example.

Imagine I’m an academic advisor who works with undergraduate students. When I meet with students, I help them schedule courses each term in consideration of graduation requirements and their academic interests.

Who is expected to learn? Undergraduate students.

+

What learning is expected? Identifying courses for their schedule.

+

When/where is learning expected? After meeting with an academic advisor at least once.

+

Why is learning expected? Students need to meet program requirements to graduate.

=

Undergraduate students will be able to identify courses for their schedule to meet program requirements after meeting with an academic advisor at least once.

OR

As a result of attending at least once with an academic advisor, undergraduate students will be able to identify courses for their schedule to meet program requirements.

Following the formula may not be enough, however. Here are some common issues you may encounter when trying to articulate learning outcomes:

5 common issues you may encounter:

1. Measuring intervention instead of learning

There’s not a problem in wanting to measure or capture satisfaction or quality of an intervention – that’s good information to know – but it’s not learning. While a help desk technician may have been friendly, if the student cannot replicate the troubleshooting steps to resolve a user error that they made, that’s important to know (i.e., satisfied with the technician, but learning did not occur).

It’s okay to measure satisfaction or quality, but also look to articulate and measure what the student will know, think, or be able to do as a result of the satisfactory or quality intervention.

2. Making too complicated or wordy of a statement

People sometimes making writing learning outcomes more complicated than it needs to be, thinking they need to use big words or make it sound very academic. Remember: These are student learning outcomes. If the student wouldn’t understand the statement, there’s a problem.

So, do just that – pilot your outcome statements with students to see if they understand what’s intended. You can also share your draft outcome statements with colleagues outside of your area for feedback, opening the door for them to share tips based on their outcomes.

3. Covering multiple outcomes in one statement.

We sometimes unintentionally capture more than one behavior in an outcome statement. The word “and” is typically a sign you’re doing too much. It may sound logical to say something like, “students will identify and utilize campus resources,” but this names two behaviors: identify and utilize.

What happens if a student can identify their school has tutoring but does not utilize tutoring services? This complicates assessment efforts. In these cases, look to separate into unique outcomes or pick the behavior you care more about (e.g., while identification is great, if you really want to know who uses the service, keep “utilize” and drop “identify”).

4. Outcomes may not be realistic given conditions

You may hope students can articulate an engaging elevator speech to a potential employer as a result of working with a career coach, but that may be the result of multiple meetings and should be stated as such.

Or perhaps you hope students will persist and graduate as the result of selecting a major fitting their career goals with an enrollment counselor. While that’s a good hope, is it really fair or appropriate to hold Enrollment responsible for a student navigating their entire college career to graduation?

Maintain scope of interventions in articulating expected learning.

5. Feeling like an exercise without connection

Learning outcomes should matter to you and your area; they should reflect what you hope or intend to happen given your interventions. If you feel like you are making things up or do not actually anticipate seeing certain knowledge, skills, or behavior, don’t write that. If you feel like your area doesn’t impact student learning at all, look to discuss with your assessment leader on campus.

Like anything else, practice makes for improvement. Additionally, assessing learning outcomes helps, too, as you’ll learn on the back end how outcome statements can shape measure or interpretation of data.

As mentioned, engaging students in the process can be really beneficial from a language perspective. More important than helping you, involving students can help them understand what is being asked or expected of them as a result of specific interventions. It can also give them a better or more realistic understanding of relationship of how their experiences relate to student learning and assessment.

All the best as you look to articulate outcomes anew or examine current outcomes to be appropriately written.

How have you created learning outcomes? Tweet us at @themoderncampus.