Is your leadership programming getting stale?

Maybe you’d like to find some different formats for your student leadership series… besides hosting yet another workshop. Experiential learning is one method of changing up your leadership development opportunities.

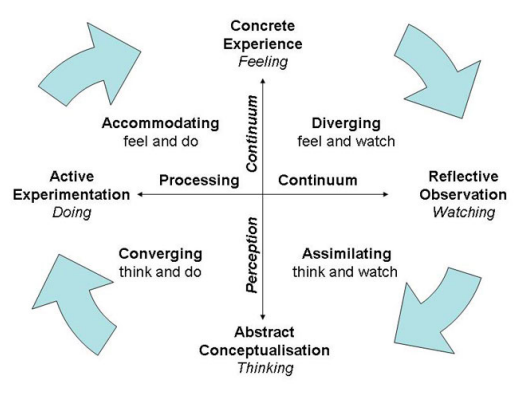

The experiential learning cycle was developed by educational theorist David Kolb as a way of examining how students apply abstract concepts to different situations.

There are four stages in the learning cycle:

- Concrete Experience: A new experience or situation is encountered or an existing experience is reinterpreted.

- Reflective Observation of the New Experience: Inconsistencies between the new experience and current understanding of a concept are examined.

- Abstract Conceptualization: Reflection gives rise to a new idea or a modified understanding of an existing concept.

- Active Experimentation: The learner applies their idea(s) to the world around them to see what happens.

illustration of Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle

A well-designed experiential learning program will guide students through all four stages of the cycle. This is important because each stage engages one or more of the learning styles Kolb identified.

Students embody different learning styles, (diverging, assimilating, converging, and accommodating) depending on where they fall on the Processing Continuum (how they approach a task) and the Perception Continuum (their emotional response to new information or experiences).

I’m going to show you how experiential learning can add variety to your leadership programs.

Case Study Competitions

In a case study competition, students devise a solution (often envisioned as a product or a process) for a problem or scenario that is grounded in real-world concerns. Here’s how you could structure a case study program to meet the needs of a college leadership program:

In an introductory session, explain the timeline for the competition, outline the problem or scenario that students are trying to solve, and articulate how the solution should be presented.

Depending on the scenario, this may be a physical model that the students build, a written proposal to get funding for a service, or a diagram that explains how they would improve a process.

Some problems or scenarios that might be applicable to your students’ leadership development include:

- having students draw up a floor plan for a community center and explaining what sort of programs or services the center would offer (This would challenge students to research issues that are prominent in their local area, along with best practices for building community.)

- having students brainstorm a service that they think a department on campus should offer or a way an existing service could be improved (Students should identify what unmet or underserved needs they are addressing and sample programs from other institutions.)

Be sure to provide a packet of information that includes everything that was presented in the introductory session, as well as a set of discussion questions to guide students’ research and any additional background information they may need.

For example, for the community center project, you could include some demographic data that highlights how many people in the community are food insecure, how many people need support with substance abuse, or the ratio of children to adults in the population.

I highly encourage you to connect each team with a mentor to coach them through the process. A good mentor will pose questions throughout the research process, helping students think outside the box and connect the project to personal experiences.

The final session will involve students presenting their solutions to their peers and a panel of judges. The judges could be faculty, staff, or members of the local community. Judges would use a rubric to grade each solution along various metrics — such as creativity, use of research, and the feasibility of the solution. Hint: connect the scoring criteria back to your learning outcomes!

Don’t forget to give out certificates to the winning team and celebrate everyone’s collective ingenuity at the conclusion of the program.

The Power of Circles

The circle is a universal symbol of completeness and harmony. Program facilitators frequently have participants sit in circles because this shape contains the group’s energy and fosters human connection. There are many experiential activities that take advantage of the dynamics that a circle creates.

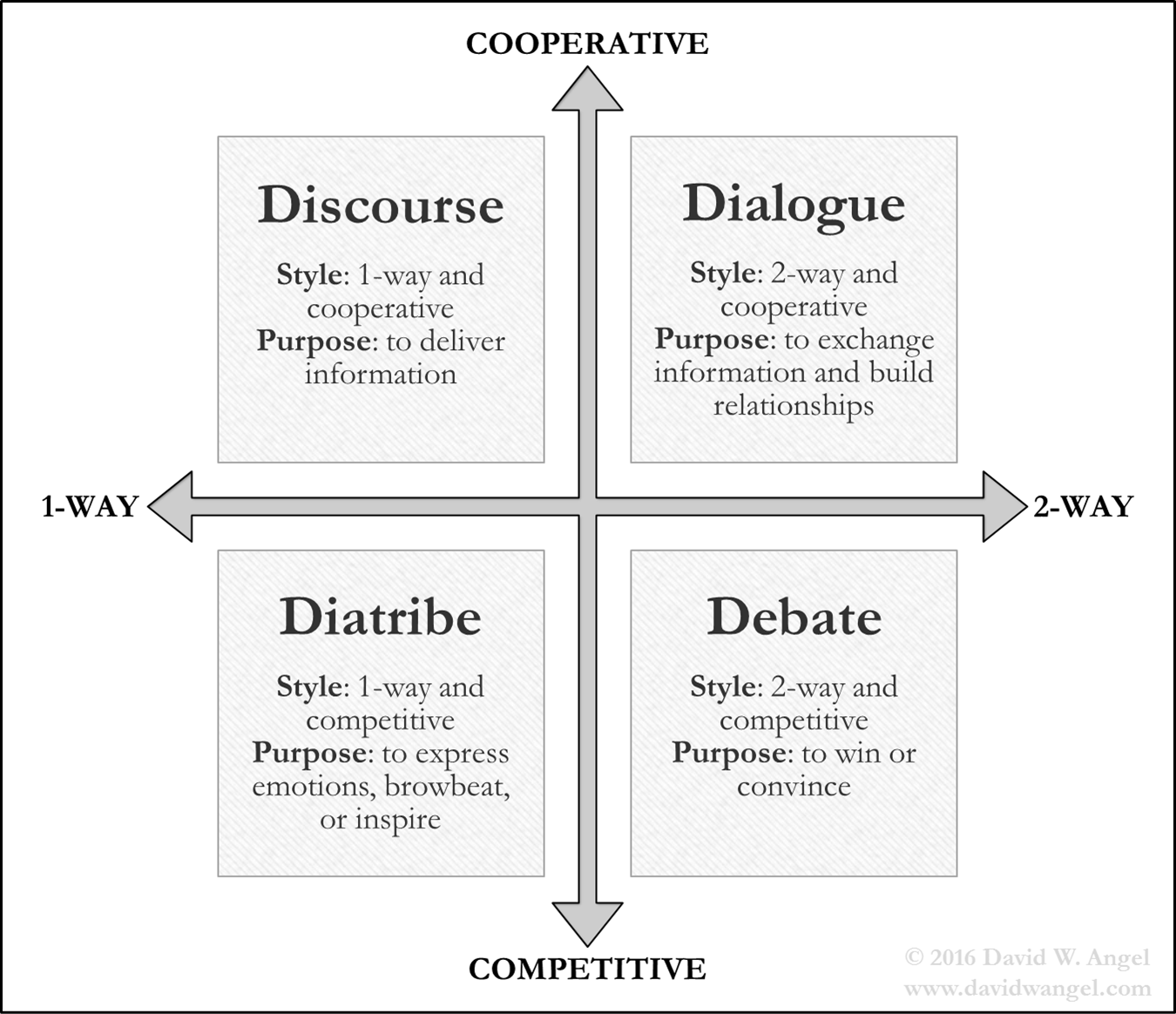

To fully appreciate what each of the following activities has to offer, the diagram below defines what types of conversation might go on in these circles. This table from the University of Washington further defines some of the terms.

World Cafe

A World Cafe session combines the benefits of small roundtable discussions (discourse) with the cumulative nature of community wisdom.

During the session, students cycle through a series of tables, each with a prompt written on a paper tablecloth or pieces of easel paper. When I run these types of sessions, there is no facilitator at the table; the process is entirely driven and guided by the students.

As they discuss each prompt, students are encouraged to write, draw, diagram, and otherwise document their insights onto the paper. The recorded community wisdom is explored when the whole group debriefs at the end of the session.

If you need some inspiration for prompts, the organization Ask Big Questions has got you covered. Each year, they publish a series of questions that are designed to spark conversations that help people connect to each other. You can either use the questions with the World Cafe format for organic conversations or download the Ask Big Questions discussion guides for more structure.

TED Talk Circles

If you’re looking for something that requires less preparation, TED Circles may work better for you. To start, students will watch a TED Talk before or during the gathering. Following the video, the facilitator will ask the group questions; (TED provides some questions or you can make up your own.) Depending on the nature of the questions you select, you can steer the conversation towards a debate, a discussion, or a dialogue.

Because this program is less labor-intensive, you can hold multiple TED Circles during the semester. For each gathering, have one or two students serve as peer facilitators so that every student eventually has a turn.

Before beginning the series, it would be a good idea to hold a workshop on facilitation basics for your students.

Storytelling

Storytelling is one of the oldest styles of communication. Storytelling is compelling because it helps listeners form an emotional connection to the speaker.

Think about it; which do you tend to remember best: statistics and statements, or stories?

Storytelling is all around us. Keynote speakers weave stories into their speeches to emphasize a point, job interviewees tell stories about how they came to love their line of work, and companies share stories of happy customers in their marketing campaigns.

Student affairs professionals can use the storytelling activities that are explained below to help students talk about their journeys as leaders.

Story Circles

A story circle focuses on personal reflections rather than public speaking. During a story circle, students each share a story about their experience related to a given topic. It is not a discussion; students are not allowed to comment on anyone else’s stories, only share their own experiences.

The circle concludes with a closing ritual. One or more of these ritual examples may be right for your group:

- Each student shares what they are feeling in the moment or what they learned.

- Recite a mantra, poem, cheer, or chant that relates to the topic.

- Do a breathing exercise or meditation, or have a moment of silence.

Prior to the program, you might have students draw a map that represents their journeys as leaders up until this point. The map could include opportunities that they had to serve as a leader, mistakes that they’ve made along the way, and mentors who’ve encouraged them.

Make sure that whoever facilitates the story circle is prepared to support students who might be triggered by traumatic memories. Unlike PecheKutches (discussed below), story circles are unscripted and require a facilitator who can trend the delicate balance of encouraging students to be vulnerable and safeguarding their emotional wellbeing.

PechaKucha Presentations

A PechaKuche presentation infuses public speaking practices with storytelling. It follows a simple format: students give a presentation through exactly 20 slides, with the slides automatically advancing after 20 seconds. This gives students six minutes and forty seconds to present. Both PowerPoint and Google Slides can be programmed to automatically advance this way.

Paul Gordon Brown identified five outcomes for students who present a PacheKutche:

- It forces you to simplify and hone your message.

- It teaches you discipline.

- It teaches you better slide design.

- It makes you practice.

- It improves your public speaking skills.

A PacheKutche-style program might be used as a capstone presentation in a leadership course, during which students share how they’ve grown since starting the program. You could also give students prompts so that they can share a story related to an aspect of leadership, such as being resilient, building community, or advocating for change.

This guide provides tips for designing a PacheKutche and this infographic illustrates the seven types of storytelling structures that students might use in their presentation. Feel free to share these resources with your students.

Hopefully, these experiential programs have given you some ideas for reinvigorating your student leadership initiatives. The human mind craves variety, and these examples will provide just that!

To truly connect experiential programming with post-graduation success, you should design each program with learning outcomes in mind. Better yet, gamifying learning can incentivize students to sign up and keep coming back. It may sound complicated but, with Presence’s Experience features, you can automatically track student participation and learning, plus prompt students to engage in self-reflection. It’s all designed to help you maximize each and every co-curricular program!

What other experiential program ideas do you love? We’d love to learn from your successes! Connect with us on Twitter @themoderncampus and @JustinTerlisner.